After having a few new sexual partners since her last STI screening, Millie Zehnder, then a 19-year-old sophomore at Florida State University, wanted to do the responsible thing and get tested again. She immediately thought of the clinic she walked by every day on her way to class. Each Wednesday, at an outreach event for campus organizations, smiling representatives from this health center advertised free or low-cost pregnancy and STI testing. Usually they wore scrubs. The popcorn machine on their table emitted the comforting aroma of a movie theater. Millie thought they seemed nice.

So she booked an appointment. But when she got to their office—right across from campus—she was surprised to see a Bible quote in flowery script on the wall. Soon, she was ushered into a “counseling” room, asked about her religious views, and told the story of Adam and Eve. Then, while her STI tests were prepared, a staffer gave her an iPad loaded with a slideshow that featured graphic images of botched abortions and untreated STIs. “They showed me gruesome photos and told me sex is bad and abortion is bad,” Millie says. At one point, they asked her to sign a chastity pledge. “I left that place crying. They wanted me to comeback for a follow-up, and I was like, ‘No way.’”

Millie had been roped in by a crisis pregnancy center, or CPC—one of approximately 2,750 anti-abortion clinics across the country that offer free or low-cost medical services with the intent of convincing women not to terminate their pregnancies. Often unlicensed, largely unregulated, and staffed mostly by volunteers (versus doctors or nurses), many use deceptive marketing, shame tactics, and incomplete or just plain wrong health info to make their case. Because they don’t offer a full range of medical services or even birth control, they’re not real clinics—and they may prevent a woman from getting the care she actually wants or needs (some CPCs have been accused of lying about how far along women’s pregnancies are to get them to delay their decision until an abortion becomes harder and more expensive to obtain).

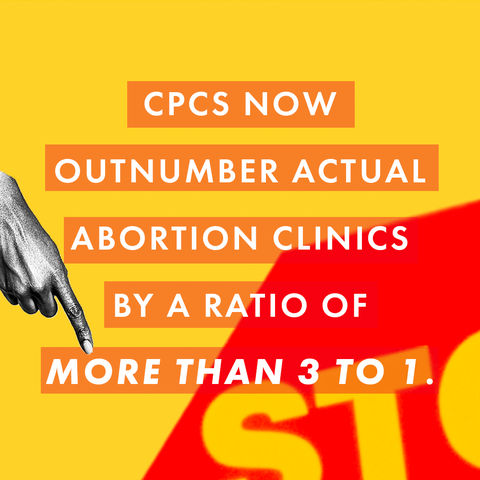

Flourishing under the full support of the Trump administration, not to mention more cash from state governments, CPCs now out-number actual abortion clinics by a ratio of more than 3 to 1. “CPCs have been empowered and given a space to thrive,” says Diana Thu-Thao Rhodes, the director of public policy for Advocates for Youth. No surprise that their tactics are getting bolder—and increasingly, they’re aimed at vulnerable college students. Here’s what you should watch out for.

Kelsey Denny, now 20 and a junior at Penn State University, says a CPC sets up shop near her school’s fraternity houses on the weekends, handing out hot dogs, grilled cheese sandwiches, and hot chocolate. Last year, at the University of Georgia, a pregnancy center offered to cater tailgates for the big Auburn football game. Other CPCs advertise at student events or on the backs of stalls in campus bathrooms. No wonder that when Kelsey and many of her friends were looking for a place to get STI tests, they ended up at one. “They make themselves seem like the obvious place to go,” she says.

CPCs are known for opening near abortion clinics to intercept their patients. But Andrea Swartzendruber, PhD, an assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Georgia, analyzed the locations of CPCs in Georgia and discovered that they actually cluster around public high schools and universities. “I’ve heard them talk at their conferences about this strategy,” Swartzendruber says. (CPCs may even sponsor college parenting groups.)

To get on campus, a pregnancy center might partner with or create a student group in order to establish satellite offices on school grounds, like they have at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln and the University of Colorado at Boulder. In other cases, like at Metropolitan State University of Denver, student-group status allows them to park a mobile clinic on campus. “Oftentimes even administrative staff at the universities don’t know the differences between real clinics and fake clinics,” says Rhodes.

These clinics aren’t illegal, says Kelli Garcia, director of reproductive justice initiatives and senior counsel at the National Women’s Law Center, which makes it hard to get rid of them. But that’s not stopping young activists from trying. Recently, Advocates for Youth and other organizations held a week of action, during which hundreds of students researched and exposed the fake clinics near or at their schools and strung up banners to spread the word that they’re not legit medical facilities. Others are petitioning their universities to limit the ways CPCs can advertise on campus. “Now that I know about what these fake clinics do,” says Kathryn Ammon, a 21-year-old senior at the University of Kansas at Lawrence, a city where two CPCs operate (but where the last Planned Parenthood closed in 2010), “I feel like I have to take action.”

Brittney was 23 years old and pursuing a degree in education in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, when she learned she was pregnant. “I was freaking out,” she recalls. Because she had no health insurance, she was relieved to discover a local clinic advertising no-cost reproductive healthcare. When she went in for an appointment, “this lady was really sweet and asked me what I was thinking. I said I was thinking about abortion,” Brittney recalls. The woman’s reaction shocked her. “She told me that if I took the abortion pill, I would never be able to have children.”

The so-called abortion pill—aka mifepristone, which when taken in conjunction with a medicine called misoprostol is FDA-approved to end pregnancies up to 10 weeks—is safe and effective, with a lower rate of adverse complications than Tylenol. Nonetheless, Brittney remembers the CPC staffer pleading with her: “Don’t do this. Don’t do this. Don’t do this.”

CPCs are focused on medication abortion because it’s used in roughly 25 percent of abortions—a number sure to grow as video doctor’s appointments and e-commerce options expand and actual abortion clinics lose funding. As more women take the pills at home, they’ll be able to avoid the restrictions placed on abortion by some states (like the requirement that women view an ultrasound first). CPCs know this, so they’re doing everything they can to scare women off of mifepristone.

These groups’ websites and pamphlets often list or exaggerate the medication’s potential complications, which are rare. “They’ll talk about breast cancer or emotional problems that stem from medication abortion,” says Alisa Von Hagel, PhD, an assistant professor of American government at the University of Wisconsin at Superior and an expert on the public discourse around abortion. “But these claims are based on faulty and misleading information.”

Some CPCs push so-called abortion reversal, in which large doses of progesterone are taken to halt a medication abortion midway through the process. But this is not scientifically proven to work. “Whether they’re talking about emotional problems resulting from abortion or abortion reversal, it’s all pseudoscience,” says Von Hagel.

According to a 2018 report issued by the Charlotte Lozier Institute, an anti-abortion public-policy research group, CPCs now have more than 100 mobile units nationally, fielded by both larger organizations and smaller ministries. These units allow them to better target college students and low-income women. Two main anti-abortion organizations outfit vehicles with ultrasound machines, exam tables, and waiting areas. These vans and RVs offer transvaginal ultrasounds—often without being licensed (only 11 percent of CPC volunteers are medical professionals, per the Lozier report; one of the groups that fields the vans claims a nurse is always present).

An abortion provider in Texas who requested anonymity said that an “old minivan” hawking free ultrasounds outside her clinic was recently replaced by an SUV. The vehicles concern her, because “more than one of my patients in the past month has been told by a CPC that she would die from an abortion,” she says.

CPCs are also using tech tools to target women virtually. A network of anti-choice consulting groups helps them with their social strategy, which often includes posting inspirational quotes on Facebook and Instagram. They might also use social-media ads and search engine optimization.“This is on the rise, and it’s a big part of how they reach young people,” says Rhodes.

At least one CPC network employs “geofencing”around Planned Parenthood and other reproductive-health centers, which uses GPS data to advertise to women whose phones enter these spaces. In 2017, Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey barred this practice in her state. Her office told Cosmopolitan that using private health info—like your pregnancy status—to advertise to you without your consent is abusive and deceptive.

Even Siri, your iPhone’s personal assistant, is confused. “If I ask Siri where I can get birth control, I get two responses—one is a CPC down the street and another is a CPC 22 miles away,” says Swartzendruber. (Apple did not respond to Cosmopolitan’s requests for comment.)

CPCs are also developing apps. Obria Direct, run by a multi state network of CPCs, seeks to “intersect these girls while they search online” for information related to unintended pregnancy, according to its website. The app seems to be replicating Planned Parenthood’s strategy, which includes live chats with providers. Young women may not even realize they’re communicating with an anti-choice group that doesn’t actually offer birth control or abortions.

That is the scariest part, according to Justine Sandoval, an organizer for NARAL Pro-Choice Colorado. “These fake clinics may look like the opposite of the in-your-face fetus pictures you see outside abortion clinics,” she says. “But they’re the same people—just with better branding.” ■

This story appears in the February 2019 issue of Cosmopolitan on newsstands now. Click here to subscribe to the digital edition.